The Story of Chromium: Part 2

The Story of Chromium: Part 2

In the Story of Chromium: Part 1 we alluded to the fact that this element is critical in making many other types of steel. In particular we touched on its ability to make steels “Stainless”.

Background to Chromium in Stainless Steels

To be considered a stainless steel, the basic steel must contain a minimum of 10.5% chromium. This chromium forms a passive, “self-repairing” layer of chromium oxide on the steel's surface, which protects the underlying steel from corrosion. “Self-repairing “means that if the surface oxide layer is scratched or damaged, it will quickly reform in the presence of oxygen. This process of forming and reforming the chromium oxide layer is known as passivation. The heat of welding can can damage this natural protective layer, making the weld area vulnerable to corrosion. It is therefore necessary to passivate after welding using a chemical process to restore and enhance the corrosion resistance of stainless steel. Passivation removes iron particles and the damage left from welding, while promoting the reformation of the protective layer that shields the metal from corrosion.

With regard to steels, we can call stainless, it’s important to note that there are five different types and these are.

- Those with chromium and enough nickel to remain metallurgically austenitic throughout the temperature range. Austenitic stainless steels.

- Those with high chromium levels that have a ferrite micro structure. Ferritic stainless steels.

- Those with lower chromium levels that form the hardened martensite micro structure. Martensitic stainless steels.

- Those with chromium and intermediate nickel levels where there is a mixture of austenite and ferrite microstructures. Duplex stainless steels

- Those that use a particular metallurgical mechanism to impart strength and are known as PH, or precipitation hardening stainless steels.

All these stainless steels are magnetic to some degree except for the austenitic type, which is non-magnetic.

Figure 2 illustrates a partially fabricated and finished hydro turbine runner in martensitic stainless steel. The martensitic stainless was selected for the material’s high strength, hardness, toughness, and resistance to corrosion and cavitation.

Since we have these five differing types then we have five different welding approaches when we come to join them. These approaches have already been discussed in this forum and are given in the links shown at the end if this article. Please refer to them for the weldability aspects of stainless steels.

Role of chromium in low-alloy steels

In non-stainless steels, chromium is essentially a hardening element. It is often used in combination with nickel (a toughening element) to produce improved mechanical properties. Chromium significantly increases a steel's hardness, wear resistance, and strength, especially at high temperatures.

Along with other elements like manganese, nickel, vanadium, and niobium, chromium contributes to the enhanced mechanical properties and durability that define so called High Strength Low Alloy (HSLA) steels. For example, the Canadian Steel, CSA G 40.21 type 350A steel contains up to 0.70% Cr

Many common grades of low-alloy steels contain chromium. Good examples are the AISI nickel chrome molybdenum series such as 4140 and 4340 that contain 0.7% to 1.10% chromium. These alloys are used in landing assemblies, heavy equipment, gears and axles.

Chrome Moly Vanadium Steel for Higher Temperature Service (Creep)

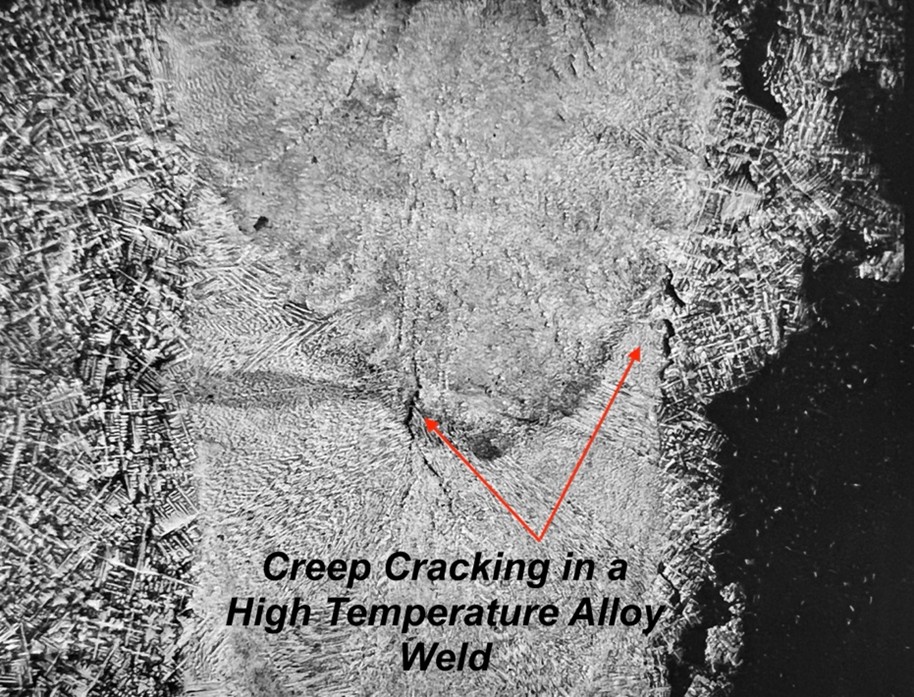

At high temperatures, and over time, metals can suffer from creep. Creep is the gradual, time-dependent deformation of a metal, under stress at elevated temperatures. This can lead to eventual failure of components in high-temperature applications like boiler parts or engine parts. Creep cracking is illustrated in Figure 3.

Chromium-molybdenum creep resistant steels usually have chromium contents between 0.5 to 9% and are used for pressure vessels and piping in the oil and gas industries and in fossil fuel and nuclear power plants.

Three general types of creep-resistant low alloy, chrome moly steels are shown in Table 1, together with typical uses and temperatures of operation

|

Alloy |

Temperature of Operation in deg C |

Typical Applications |

|

1%-1.25% Chromium and 0.5% Molybdenum |

510 |

Steam Generators and Tubing |

|

2.25% Chromium and 1.0% Molybdenum |

650 |

Petrochemical and Power Generation Industries |

|

Modified Chromium /Molybdenum Steels with micro additions of vanadium, niobium, titanium and boron |

450 to 600 |

Steam Turbines and Hydrogen containing environments |

Table 1. Types of Chrome Moly steel with Temperatures of Operation

As the alloy content increases in these materials then so does the hardenability and, as a consequence, Hydrogen Induced Cold Cracking (HICC) can be a factor during welding . These alloys need to be treated with respect and low hydrogen welding processes and/or consumables are therefore essential. Preheat is necessary for most of these Chrome Moly steels and many specifications will contain guidelines for preheat levels and further guidance to prevent “so called” reheat cracking which is a phenomenon with these materials.

Welding consumables for Cr-Mo steels must match the base metal's composition, using specific AWS-designated electrodes (e.g., E8018-B2 for 1¼Cr-½Mo steels) or filler metals (e.g., ER90S-B9 for 9Cr-1Mo steels) to ensure proper strength and resistance to hydrogen-induced cracking. The correct consumable choice depends on the specific chromium and molybdenum content of the base steel, with lower carbon versions (like E8018-B2L) which offer enhanced crack resistance.

Examples of Superalloys that contain Chromium

Inconel 718: A common nickel-iron-chromium superalloy known for its excellent mechanical properties and weldability, though it requires careful control to avoid Laves phase formation and microfissuring.

Alloy 625: A nickel-chromium-molybdenum alloy that is easily welded and used in high-temperature and corrosive environments.

Hastelloy: A family of nickel-molybdenum-chromium alloys that are tough, formable, and weldable.

These alloys have already been touched on in our recent “Story of Nickel Part 2” and readers are asked to reference that article in the link below.

Mick J Pates IWE

President, PPC and Associates

Read more:

https://www.cwbgroup.org/resources/articles/weldability-of-differing-kinds-of-stainless-steel-part-1

https://www.cwbgroup.org/resources/articles/weldability-of-differing-kinds-of-stainless-steel-part-2

https://www.cwbgroup.org/resources/articles/the-story-of-nickel-part-2